Does it Pay to Spend Time on Getting to Know your Team Members? The Effects of Inter-Member Acquaintanceship Level in GVTs

Does it help when team members know each other at a personal level? Does it make sense to spend time getting to know your team members?

Research in economics shows that giving people even a brief opportunity to get to know each other greatly improves individual and group performance. For example, a series of experiments have been conducted with the Ultimatum Game. The game goes as the following:

One player, the Giver, is endowed with a sum of money, for example, 10 dollars. The Giver is tasked with splitting the money with another player, the Receiver. Once the Giver communicates his offer, the Receiver may accept it or reject it. If the Receiver accepts, the money is split per the proposal; if the Receiver rejects, both players receive nothing. Usually, the Givers offer about $3 and the Receivers accept. Even though the offer is not fair, the Receiver tends to accept because otherwise both players will lose all the money. However, if the Giver offers too little, usually less than $2, the Receiver tends to reject the offer to pushing the unfair Giver, even though it means a loss of money for both parties.

In the experiments with the Ultimatum gave, the project participants would be assigned to two conditions. In the control condition, they would spend about 5 minutes doing random multiplications or another task not related to the game. In the treatment condition, the participants would spend the time getting to know each other (e.g., sharing a childhood memory, or sharing about their hobbies). When the game is played, the players who spent the time getting to know each other are more likely to make more equal offers (offer closer to 50-50), and the Receivers are more likely to accept the offers, and in the end, the dyads are more likely to be left with more money jointly.

Similar improvements in performance following an acquaintanceship session have been observed in various other experiments that involved negotiations or the need to collaborate. Players who had the time to get to know each other tended to cooperate more, display higher levels of trust and satisfaction, and ultimately better results.

In the X-Culture project, the teams have a limited period of time (about 8 weeks) to solve a complex international business project. Our main research question is:

Is it worthwhile allocating part of the project window to allowing team members to get to know each other or is it better to waste no time on acquaintanceship and get right to work?

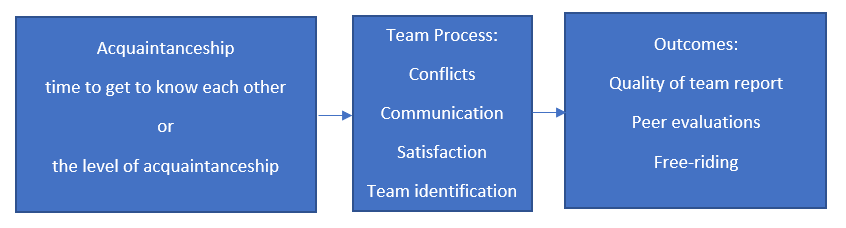

Specifically, we would like to explore if teams where team members are given an opportunity to get to know each other, and if team members who are more acquainted with their team members indeed perform better, and if so what is the mechanism by which the acquaintanceship level affects individual and team performance.

Hypotheses

- Giving team members time to get to know each other will improve team dynamics and performance.

- Teams where the average level of inter-member acquaintanceship is higher will display better team dynamics and performance.

- Team members who are better acquainted with their team members will display higher levels of satisfaction, team identification, and ultimately higher levels of performance, including a higher likelihood of being elected a team leader, and receiving higher peer evaluations.

- Team members who are more known to their team members will receive higher peer evaluations.

Model 1. The Role of Acquaintanceship on Team Performance

Levels of Analysis

The hypotheses can be tested at two different levels of analysis.

Cohort Level:

Control: The cohort is given no time for the team members to get to know each other. The teams are required to get right to the task itself.

One Week: The cohort is given one week for the team members to get to know each other before they are required to start working on their business task. The teams are prompted to spend this time getting to know their team members by administering an acquaintanceship test at the end of the first week.

One Week: The cohort is given two weeks for the team members to get to know each other before they are required to start working on their business task. The teams are prompted to spend this time getting to know their team members by administering two acquaintanceship tests at the end of the first and second weeks.

Indicators of team performance and dynamics will be compared across the experimental conditions. Presumably the cohorts that were given time to get to know each other will display higher levels of satisfaction and motivation, team identification, report fewer conflicts, give each other higher peer evaluations, and ultimately write better reports.

The tests can be as simple as comparisons of cohort averages, either by the teams of a t-test or ANOVA.

A more sophisticated test will require multivariate tests with controls for other factors that may affect team dynamics and performance, such as demographics (age, gender), level of studies (% MBA students), prior international experience, CQ, etc.

An even more sophisticated test may test the mediating effects (acquaintanceship affects team dynamics and attitudes, which in turn affect performance).

Complicating factor: the quality of the report may need to be re-evaluated by an independent group of raters so that each rater evaluates a randomly selected set of reports from each cohort. Currently, raters rate reports only within one cohort at a time. This may obscure inter-cohort differences as raters tend to evaluate reports not in absolutely but in relative terms (compared to other reports in the pile).

Individual level:

The results of the acquaintanceship test are used to measure how well (1) each team member knows his/her team members and (2) team as a whole knows the team member.

The relationship between the level of the acquaintanceship and various indicator of individual performance will be assessed.

Presumably, team members who know/are known by their team members better will:

- Display higher levels of satisfaction

- Identify more with the team

- Will show a higher level of satisfaction and motivation

- Will be more likely to be elected team leaders

- Will be less likely to be excluded from teams

- Give/receive higher peer evaluations

The tests can be as simple as OLS regression with the acquaintanceship tests as the main predictor and controls for demographics, technical and language skills, and prior international experience.

A more sophisticated test may also test for mediation (acquaintanceship – attitudes and effort – performance).

Team Level:

The results of the acquaintanceship test are used to measure how well team members know each other.

The relationship between the average team level of the acquaintanceship and various indicator of team dynamics and performance will be assessed.

Presumably, teams where team members one another better will:

- Display higher levels of satisfaction

- Display higher levels of team identification

- Show a higher level of satisfaction and motivation

- Give each other higher peer evaluations

- Write better-quality reports

Caveat: It may be interesting to test if the variance in how well team members know each other (the SD of acquaintanceship test results within the team, as opposed to the average) plays a role. A high variance would indicate that some team members know other team members well, while other team members don’t. These differences may create outcasts, which can damage team dynamics and, ultimately, performance.

The tests can be as simple as OLS regression using team-aggregated data with the team-average acquaintanceship tests results as the main predictor and controls for team-average demographics, technical and language skills, and prior international experience.

A more sophisticated test may also test for mediation (acquaintanceship – attitudes and effort – performance).

Other Study Considerations

- This semester, in the late track, we’re able to allow 3 weeks to get to know your team. It just happened to be so that we have one extra week, so the plan is to allow this time for non-task related activities (i.e., getting to know each other). It may be worthwhile waiting with the final results until we have this batch of data.

- It will be a much better study if we can show that spending time getting to know each other aids team performance. However, it is still an interesting story if the results show that it does not matter how well the team members know one another. It is counter-intuitive, but it is an important finding that maybe it’s better not to waste time getting to know each other and instead get right to the business.

- While we have the data and know how to test the hypotheses and write up the results, and the practical implications of the study are very obvious, the theory and lit. review parts may require a lot of work. I personally do not see much need for wrapping this study in a fancy-sounding theory by some famous guy from the 1960s. We have an important research question at hand, an obvious hypothesis (getting to know each other help), and hopefully soon a set of compelling results (yes, it does). If nobody proposed a theory with a fancy name, I don’t see a problem with us giving a fancy name to this hypothesis. It will not diminish the value of our findings.

However, if there is already a theory out there that explains why getting to know each other helps, it would be embarrassing if we don’t review it in the paper. Also, most journals will probably be more likely to publish the paper if it is based on some know theory with a fancy name by a famous scientist.

Either way, we have to conduct a thorough search.

- It is important to conduct a thorough search for literature in multiple disciplines. I know that behavioral economists studied this issue, so we must check that literature. However, it is very possible that there is more on the topic in psychology and management literature.

If no studies have directly addressed this question (how much time the team should devote to getting to know each other), our study may be a revolutionary one (the first one to show the effect). However, it will be embarrassing if we claim that it’s the first study, and it turns out there have been many more before us. It is possible there have been many more, and if so, it is important we not only review them, but also explain how ours is new (e.g., new different sample, new different task, larger sample, more controls, more precise estimates of the effects, etc.).

- Finally, we should decide it will be a multi-study paper (cohort, team, individual-level studies), or if it will be three different papers. It’s probably best to write one multi-study paper, but there may be room for multiple papers.